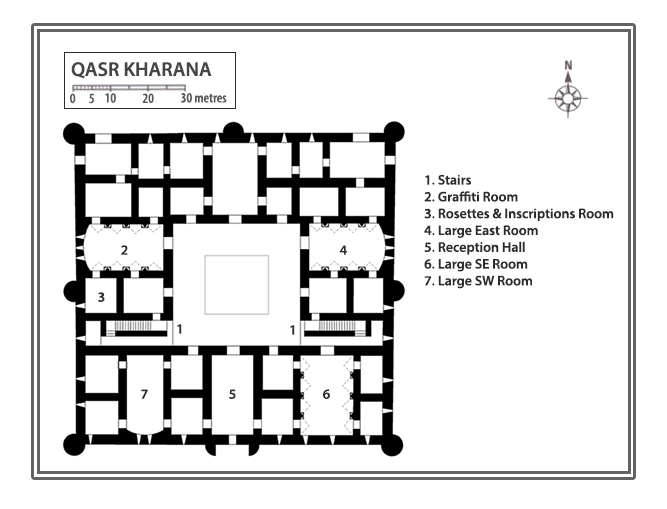

60 kilometres East of Amman on highway 40 in an arid part of the Syrian-Jordanian desert, Qasr Kharana welcomes tourists as one of the Desert Castles in this region. It is square, with each side 35 metres long. This unit was often used as a module, being multiplied by two and sometimes by four for this kind of construction. Its plan is typical: a courtyard surrounded on two levels by rooms arranged as accommodation units, or bayt. In this case, they are of the type Creswell defines as “Syrian”, as opposed to “Persian”: four rooms laid out two by two around a central courtyard which provides the sole access.

While the Desert Castles have their origin in the fortified or rural Roman-Byzantine architecture of pre-Islamic Syria, Qasr Kharana stands out because of features inherited from Sassanid Iran: squinches at points of transition, and half-domes – set on groups of three engaged half-columns with neither bases nor capitals – covering rectangular spaces. Among the many types of vaults, some – with transverse arches resting on three colonnettes – are reminiscent of such pre-Islamic Iranian sites as Ctesiphon and Sarvistan, although the latter may in fact date from the early days of Islam.

Although the Syrian castles are often bigger – 70 metres square –there are in Iraq several buildings on a similar scale to Qasr Kharana, which has four corner towers, a semicircular buttress in the middle of each wall and a single entry.

This system was adopted in the Maghreb from the 9th century onwards in such buildings as the Ribat in Susa, but the intention there was defensive, whereas Qasr Kharana was certainly a Bedouin meeting place with no military function: its loopholes were solely for ventilation and decoration. Ornamentation at Qasr Kharana is limited in terms of quantity, materials and space, as at the later palace of Ukhaydir.

On the outside bricks are laid at an angle of 45° recalling the minaret of the Grand Mosque in Raqqa. The most striking decorative feature, however, is the stucco work over the entrance and on the upper floor. During this period carved or moulded stucco ornamentation was widespread from Afghanistan to Spain. Very popular with the Romans, it reappeared in Carolingian Europe – in Germigny and Cividale, for instance – at a time when there was very close contact between Orient and Occident.

The decoration is for the most part very simple. Some of the motifs, like the combed examples to be found at the entrance and in the stairwells, and the saw-tooth patterns on the arches, also occur on many kinds of utilitarian ceramic objects, both European and Islamic. The “fleur de lys” on certain roundels in the bedrooms seem more distinctive but are also present in the Dome of the Rock.

The castle is today under the jurisdiction of the Jordanian Ministry of Antiquities. The kingdom’s Ministry of Tourism controls access to the site via the new visitor’s centre, charging an admission fee of JD 3 to the site during daylight hours.

The castle was built in the early Umayyad period by the Umayyad caliph Walid I whose dominance of the region was rising at the time. Qasr Kharana is an important example of early Islamic art and architecture. Having a limited water supply it is probable that Qasr Kharana sustained only temporary usage and there are different theories concerning the function of the castle, it may have been a fortress, a meeting place for Bedouins (between themselves or with the Umayyad governor), or used as a caravanserai. The latter is unlikely as it is not directly on a major trade route of the period and lacks the groundwater source that would have been necessary to sustain large herds of camels.

In later centuries the castle was abandoned and neglected. It suffered damage from several earthquakes. Alois Musil rediscovered it in 1901, and in the late 1970s, it was restored. During the restoration, some changes were made. A door in the east wall was closed, and some cement and plaster were used that was inconsistent with the existing material. Stephen Urice wrote his doctoral dissertation on the castle, published as a book, Qasr Kharana in the Transjordan, in 1987 following the restoration.