Situated 30km from Zarka and 60km from Amman, Qasr Al-Hallabat stands as a remarkable testament to the ancient history and cultural shifts that shaped the Near East. It is one of the most significant sites of the region, offering invaluable insight into the evolution from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages, ultimately showcasing the origins of Islamic culture. Additionally, it is among the largest and most intricately designed of the Umayyad Desert Castles.

A Roman Fort Turned Architectural Marvel

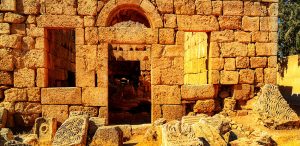

Originally built as a modest Roman fort in 106 AD, Al-Hallabat was designed to protect essential trade and travel along the Via Nova Trajana, the famed Roman road stretching from Bosra to Aqaba. Part of the Limes Arabicus defence line, it was later expanded in the 4th century AD—likely under the reign of Emperor Diocletian—into a substantial fortress featuring four imposing corner towers. It endured significant damage during a massive earthquake in 551 AD but was subsequently transformed, reflecting its long history of repurposing. The site was reimagined into a monastery and then further altered into an elegant palace during the Umayyad era.

The Main Building

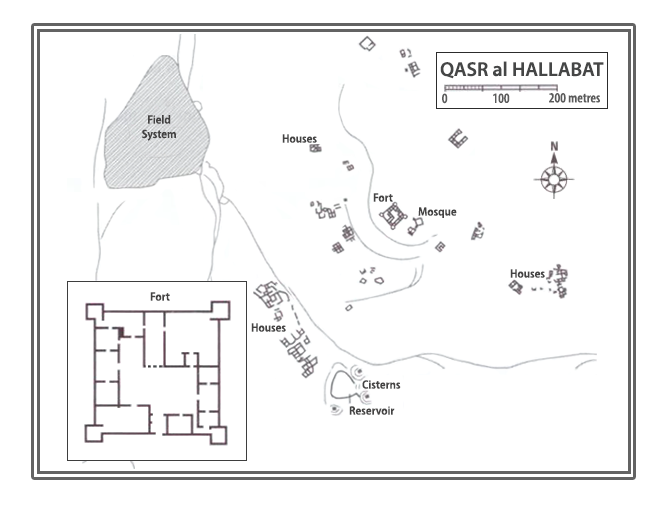

Central to Al-Hallabat’s history is its formidable main structure—an almost perfect square with each side measuring 44 metres. Its corners are anchored by prominent rectangular towers, originally three stories high and outfitted with narrow slit windows for defence and surveillance. A notable section in the northwest—incorporating remnants of an older, smaller fortress—features a classic courtyard and a well-preserved cistern, surrounded by modest yet functional rooms.

The Adjacent Mosque

Just steps from the visitor’s centre lies the site’s mosque, a modest rectangular structure that exudes historical significance. Its inscriptions, stylistically dated from the middle of the 7th to the 8th century (early Islamic era), tie the mosque back to the roots of Islamic artistry and devotion.

Hammam As-Sarah Bathhouse

Two kilometres east of the castle lies Hammam As-Sarah, a small yet intricate Umayyad bathhouse. Adorned with fine marble, vibrant mosaics, and carefully painted plaster, this bathhouse speaks to the luxurious traditions that the Umayyads cultivated. Though compact in scale, it shines in decorative grandeur, serving as an excellent example of Umayyad design.

Extraordinary Water Systems

The resourcefulness of Al-Hallabat is also evident in its extensive water management system. West of the main castle, the Umayyads constructed or revamped at least five cisterns alongside a vast reservoir. These sophisticated systems reflect a deeper understanding of the arid environment and a commitment to sustainability.

Historical Epigraphy and Artefacts

The story of Al-Hallabat is further enriched by the discovery of 146 Greek inscriptions, alongside two Nabataean texts and a Safaitic engraving. Carved onto basalt stones, these inscriptions include an imperial edict by Byzantine Emperor Anastasius (reigned 491–518 AD), documenting the administrative and economic restructuring of Provincia Arabia. These stones repurposed during the Umayyad period as building materials, reveal the layered history embedded in Al-Hallabat through every corner and crevice.

A Journey Through Time

With its dynamic transformations, intricate designs, and historical layers to uncover, Qasr Al-Hallabat is more than just a remnant of the past—it is a window into the pivotal cultural and socio-political changes of the region. From its origins as a Roman fort to its peak as a luxurious Umayyad palace, Al-Hallabat invites modern visitors to step back in time and marvel at its resilience, artistry, and enduring legacy.

Originally constructed as a Roman fortress under Emperor Caracalla in the second and third century AD, this site stands as a testament to the strategic prowess and engineering mastery of the Roman Empire. Positioned on the Via Nova Traiana—a crucial highway connecting Damascus to Aqaba—the fortress played an essential role in safeguarding inhabitants from Bedouin tribes and securing vital trade routes across the region.

By the eighth century, the grandeur of this site was profoundly transformed under the direction of the Umayyad caliph Hisham ibn Abd al-Malik. Repurposing the Roman structures, he envisioned and created one of the most magnificent desert complexes of the Umayyad era. It became a hub of innovation and culture, featuring intricate infrastructure such as a mosque, advanced water systems with cisterns and a large reservoir, and developments for agriculture, potentially cultivating olive groves and vineyards.

Today, the remnants hint at the splendour of the past. While only fragmented sections of structures, such as the mosque walls and mihrab, remain intact, the site’s significance in history is undiminished. The palace—built of black basalt and limestone—still evokes grandeur in its square design and corner towers. What remains of the decorative mosaics, frescoes, and stucco carvings offers a fleeting glimpse into the opulent artistry that once adorned its halls, reflecting a profound blend of Roman and Umayyad ambitions.

Standing in these ruins, one cannot help but feel connected to the crossroads of civilisations—a place where ancient Roman engineering met the ambition of the Umayyad caliphate, leaving a legacy etched in the stones of history.